Explainer: SA’s Health Access Zones should not exempt ‘silent prayer’

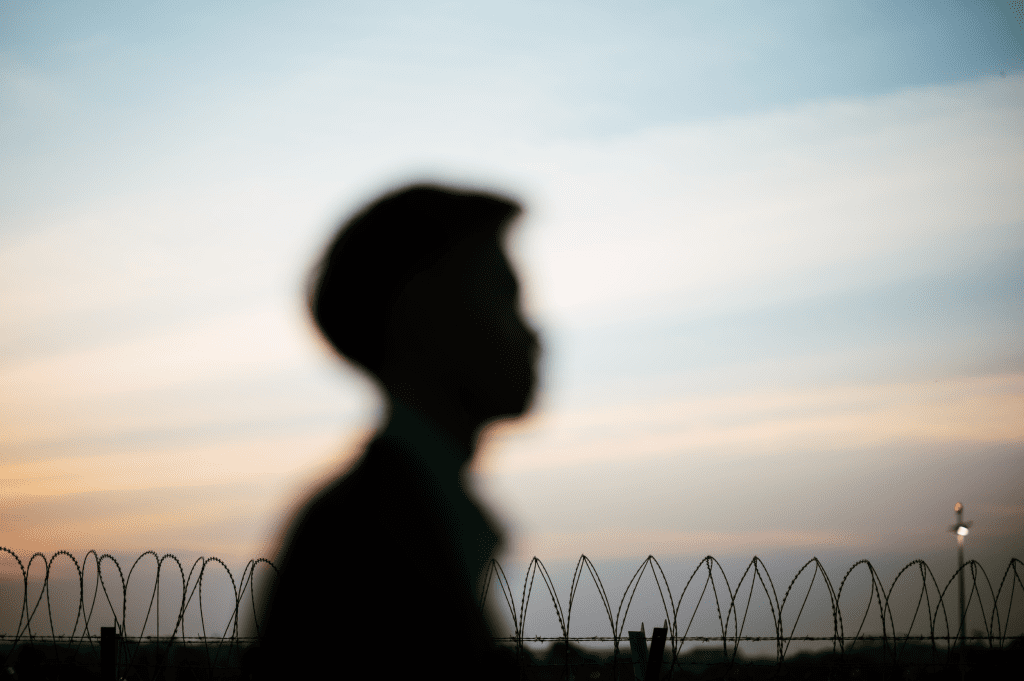

Silent prayer outside abortion clinics can be particularly harmful to women trying to access healthcare. The objects of the Health Care (Safe Access) Amendment Bill 2020 (SA) (‘the Bill’) would be completely undermined by an amendment that authorises silent prayer within a health access zone, by allowing anti-abortion activists to invade the privacy and threaten the wellbeing of patients seeking abortion care.

1. Research shows that silent prayer is harmful to patients accessing abortion care

Many studies have identified the adverse impacts of anti-abortion activities outside clinics on patients and staff, including psychological distress, anger and fear, and delays in accessing abortion or post-abortion care, which in turn increase the risk of health complications.

Critically, it has been identified that the mere presence of anti-abortion activists is a gateway factor in terms of creating distress for patients.i Silent prayer is a broad concept. It may involve one or 50 anti-abortion activists. It might involve people moving around and following patients, standing in front of a clinic’s entry and staring disapprovingly at women as they attempt to see their doctor about a private medical decision.

Clearly, such conduct will intimidate some women; cause shame, anxiety and distress for others; and even prevent or delay some patients from accessing the healthcare they need.

2. The focus of SA’s health access zones must be to prevent harm

The mistreatment of women seeking reproductive healthcare is a form of gender-based violence.ii Safe access zones have played a vital role in preventing this in Victoria, Tasmania, NSW, Queensland, the ACT and the Northern Territory.

The objects of the SA Bill recognise this. They are about protecting “the safety, wellbeing, privacy and dignity” of patients and staff outside of services that provide abortion care.iii The Bill is appropriately focused on preventing harm to patients and staff, including by prohibiting harassment, intimidation and obstruction, as well as communications about abortion that are “reasonably likely to cause distress or anxiety” (‘the communication prohibition’).iv These protections for patients would be undermined by an amendment that authorises silent prayer inside a health access zone.

An exception for silent prayer would signal that South Australia’s Parliament is willing to accept a form of conduct that is known to harm, shame, stigmatise and invade the privacy of patients seeking healthcare, and particularly women. The laws would be doomed to fail to meet their purpose – to create a zone in which patients can feel safe.

No other safe access zone law in Australia contains an exception for silent prayer.

3. The Bill strikes the right balance and should not be amended

The wording of the Bill should not be amended.

As currently worded, where silent prayer amounts to harassment, intimidation or obstruction, it will be appropriately prohibited. In other cases, police and courts will be able to look at the whole of the circumstances and determine whether someone’s communicative behaviour is “reasonably likely to cause anxiety or distress” to patients or staff. For example, 20 people circled around the entrance of a clinic praying silently and staring at patients would likely cause anxiety or distress, however, one person sitting head down praying on a bench 140 metres away is less likely too.

The approach in the Bill thus strikes the right balance between the rights of a woman trying to access health care privately and safely, and the right of an anti-abortion activist to express their religious views.

It is critical to remember that women seeking abortion care are making a private medical decision and have no choice but to enter a clinic in order to receive the healthcare they need. As the US Supreme Court has noted, they are captive to medical circumstance.v In contrast, anti-abortion activists are able to express their views in many and varied ways and places outside of the 150m safe access zone.

4. The High Court recognised the harm that silent actions can have on patients

The High Court last year upheld a communication prohibition in Victoria’s safe access zone laws as a reasonable limit on the implied freedom of political communication in Australia’s Constitution. The SA Bill contains a near identical communication prohibition.vi

The High Court decision (and a subsequent Supreme Court decision) recognises that silent prayer or vigil can be a powerful and harmful form of communication, which may fall foul of the communication prohibition as a communication that is reasonably likely to cause anxiety or distress. Importantly, three Justices of the High Court recognised that:

“silent but reproachful observance of persons accessing a clinic for the purpose of terminating a pregnancy may be as effective, as a means of deterring them from doing so, as more boisterous demonstrations.”vii

For SA’s health access zones to be effective in protecting the privacy, safety, wellbeing and dignity of patients, they should not allow any conduct that could prevent or deter patients from accessing the healthcare they need.

This explainer is not legal advice

The contents of this publication do not constitute legal advice, are not intended to be a substitute for legal advice and should not be relied upon as legal advice. You should seek legal advice or other professional advice in relation to any particular matters you or your organisation may have.

i Graham Hayes & Pam Lowe, ‘A Hard Enough Decision to Make’: Anti-abortion Activism Outside Clinics in the Eyes of Clinic Users (2015).

ii CEDAW, General Recommendation 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating General Recommendation No. 19 (2017).

iii Health Care (Safe Access) Amendment Bill 2020 (SA), proposed section 48C(1).

iv Health Care (Safe Access) Amendment Bill 2020 (SA), proposed section 48B (definition of ‘prohibited behaviour’).

v Madsen v Women’s Health Centre Incorporated (1994) 512 US 753, 768.

vi Health Care (Safe Access) Amendment Bill 2020 (SA), proposed section 48B (subsection (d) of the definition of ‘prohibited behaviour’).

vii Clubb v Edwards & Anor; Preston v Avery & Anor [2019] HCA 11 [89]. See also Clubb v Edwards [2020] VSC 49 [51].

Explainer: NSW’s proposed laws on hate crimes and places of worship

If passed, new laws in NSW would have wide-ranging implications for the right to peaceful assembly and may lead to the criminalisation of conduct which does not impact on the rights of people to practice their religion and be protected from racial or religious hatred.

Read more

Explainer: Making Queensland Safer Act 2024

The Queensland Crisafulli Government’s latest legislation, the Making Queensland Safer Act 2024 (Act), substantially changes how children are treated by Queensland’s police, courts and prisons, including by making prison sentences significantly longer. The Queensland Government concedes that the changes are ‘more punitive than necessary to achieve community safety’ and ‘in direct conflict with international law standards’. ¹

Read more

Explainer: Migration Amendment (Removal and Other Measures) Bill 2024

A legal explainer of the Migration Amendment (Removal and Other Measures) Bill 2024 , with a brief analysis of its operation. The Bill permits the Minister to direct certain people to take steps to facilitate their removal from Australia. It also prohibits nationals from certain countries from making a valid application for any visa to come to Australia.

Read more