‘Permanently temporary’ migrants are part of Australia. Labor must not fail them again

OPINION | This piece was originally published by The Guardian

Just weeks ago the Albanese government was handed a 200-page report that spelt out the failures of the migration regime in agonising detail.

The report could not have been more emphatic. It described key areas of the migration system as irrevocably “broken”, requiring “major reform” that “cannot be achieved by further tinkering and incrementalism”.

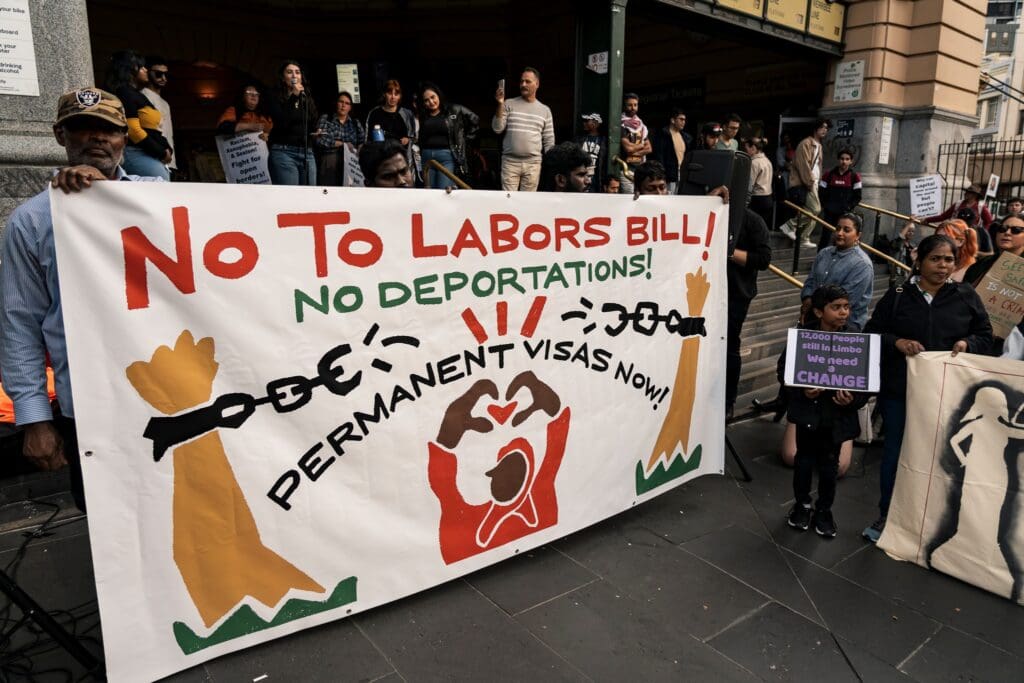

The report focused on the limbo faced by some 90,000 “permanently temporary” migrants, who have been in Australia for five or more years without a pathway to permanent residency, leaving them open to predation by bosses and landlords. It described the widespread wage theft from temporary migrant workers across the economy. It detailed the profit-hungry international education economy that takes $4bn from international students every year, often leaving them with little in return other than a massive debt.

But just as the Albanese government is poised to respond to this “once-in-a generation” examination of the migration program, we hear reports of visa “scams”, human trafficking syndicates and agents and applicants alike “gaming the system” – making it seem as though it is temporary migrants themselves who are to blame for the dysfunction of the system.

There is an eerie sense of history, and policy, repeating itself.

In 2010 the Gillard Labor government oversaw sweeping reforms to international education and skilled migration in the name of clamping down on rogue international colleges and dodgy education agents. Little consideration was given to what this would mean for students, who in the public discourse often were deemed fraudulent by association.

The result was the closure of multiple vocational education colleges, leaving students thousands of dollars out of pocket in part-paid course fees. Draconian fraud-related visa requirements were introduced that operated to fix visa holders with the consequences of their migration agent’s conduct, as though they were the same person – leading to mass visa refusals and visa holders being left in limbo as they were barred from applying for further visas for three years.

But perhaps most importantly the remodelling of Australia’s skilled migration program to screen out supposedly unqualified international students left tens of thousands of former students, mostly from India and China, in the lurch.

A decade later these former students now form the ranks of the “permanently temporary” – people who have been part of Australia for years, who have worked, made a life, had children and become part of the community, but still have no permanent right to stay.

Now, as international students return to Australia in record numbers, a criminalising rhetoric serves to remind temporary migrants of their provisional and disposable status. It reminds them that, no matter how much Australians might rely on their work or economic contribution, they will continue to be viewed with suspicion as scammers looking to undermine the integrity of Australia’s otherwise impeccable migration program.

But temporary migrants are not simply numbers on the national balance of payments. Nor are they passive victims who require law makers to step in and take responsibility for their lives. They are people who are an integral part of our community.

Any doubt about that should have been dispelled by the pandemic. We would not have had fresh produce to eat, supermarkets to shop from or even public transport if it weren’t for the work of temporary migrants.

If the Albanese government is serious about tacking the exploitation of migrant workers then it must remove the levers for exploitation in the migration system it administers. It must address the strict enforcement of visa conditions that render people vulnerable to extortion and threats by their bosses. It must provide protections for visa holders who take action for breaches of workplace laws. And it must address the inherent visa insecurity that leaves temporary workers dependent on their bosses for the hope of permanent residency.

In short, the Labor government must put the rights of temporary migrants at the heart of its migration reforms and not in the margins. Otherwise it will be poised to make the same mistake twice.

Sanmati Verma works in the Migration Justice team at the Human Rights Law Centre. You can learn more about the team’s work here.

Why we need stronger whistleblower protections

In March, Associate Legal Director, Kieran Pender was at the ACT Court of Appeal to observe McBride’s appeal – he is challenging his conviction, and the severity of his sentence.

Read more

International Women’s Day: Rights, equality, empowerment

International Women’s Day is more than an anniversary, it’s a global celebration of what has been achieved over centuries of campaigning and action by women fighting for equality.

Read more

High Court challenge launched for man facing deportation to Nauru

The Human Rights Law Centre has filed an urgent High Court challenge on behalf of a man who was scheduled to be deportated to Nauru. After filing the legal challenge, the Australian Government promised that our client would not be removed before his case was finished.

Read more